Summary: Post-Quantum Key Exchange (New Hope)

Andreis Gustavo Malta Purim¹

¹ Institute of Computing, State University of Campinas in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil. a213095@dac.unicamp.br

Disclaimer: This summary is my report for grad-level course MO421 (Cryptographic Algorithms) at UNICAMP. The objective is to explain the New Hope Post-Quantum from a begginers perspective, without sacrificing the technical content. This report was submitted on 30/06/2024 but it may be edited to add more content or clarify some parts in the future.

Also, be aware that this is the first time I add MathJax on my website. Since it’s a recent addition, it might not be as stable as I’d like.

Disclaimer 2: Sometimes, the page renders inline equations as block equations for reasons beyond our mortal understanding. Refresh thy page if that is thy case.

1. Summary

This report examines the New Hope proposal for Transport Layer Security (TLS), proposed by Erdem Alkim, Leo Ducas, Thomas Poppelmann, and Peter Schwabe at the USENIX Security Symposium 2016. New Hope was one of the Key Exchange Methods (KEM) proposals submitted to the NIST Post-Quantum Padronization competition. By implementing the Key Exchange, it would ensure that the TLS protocol was safe against quantum computers capable of breaking traditional assymetric encryption.

New Hope was based on the Ring Learning with Errors (Ring-LWE, or simply RLWE) primitive, which itself bases its security on the Lattice-based Short Vector Problem (SVP). By focusing on key optimization and security designs (reconciliation techniques, against all authority design, and others), it provided an optimized but secure way of users conecting to severs throught the internet without being at risk of quantum computers.

Hopefully, by explaining how New Hope works, I’ll also explain the basics of LWE and Post-Quantum Cryptography.

The sections of this report will be as follows:

Sections:

- Introduction to Post-Quantum Lattice-Based Cryptography

- The Basics of Ring Learning-With-Errors

- New Hope TLS Proposal

- Comparison with previous works and conclusions

- Sources and Additional Material

2. Introduction to Post-Quantum Lattice-Based Cryptography

In this section, I’ll briefly explain how assymetric cryptography worked and how (and why) quantum computers may break them. I’ll also present a new type of mathematical problem that may be used as a basis for a quantum-safe cryptography.

2.1 From RSA to Lattices

One of the fundamental pillars of the internet is the capability for two parties to exchange messages privately and securely, even if they have had no prior contact. To achieve this without any intermediaries (such as governments, internet service providers, or any devices intercepting network packets) knowing the contents of the message, these parties must establish a cryptographic key securely. This process must ensure that neither party’s private key is ever disclosed or transmitted over the network. This is accomplished using asymmetric cryptography.

For brevity, I’ll assume the reader has a basic understanding of classic asymmetric cryptography. In sum, asymmetric cryptography, such as RSA and ElGamal, relies on two parties having private keys (never shared over the air) and public keys (accessible to anyone). When one party wants to contact another, it uses its own private key and the other’s public key to generate a shared secret, which only both parties know.

A prime example is the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Let’s consider two users, Alice (A) and Bob (B). Alice and Bob agree on a large prime number $$p$$ and a base $$g$$, which are public. Alice selects a private key $$a$$ and computes her public key $$A=g^a\ mod\ p$$. Similarly, Bob selects a private key $$b$$ and computes his public key $$B=g^b\ mod\ p$$. They exchange their public keys over an insecure channel.

Alice then uses Bob’s public key $$B$$ and her private key $$a$$ to compute the shared secret $$K=B^a\ mod\ p$$. Bob uses Alice’s public key $$A$$ and his private key $$b$$ to compute the same shared secret $$K=A^b{ }mod{ }p$$. Since $$A=g^a\ mod\ p$$ and $$B=g^b\ mod\ p$$, both calculations result in the same shared secret $$K=g^{ab}\ mod\ p$$. This shared secret can then be used to encrypt further communications between Alice and Bob, ensuring that their messages remain private and secure.

The Diffie-Hellman key exchange is secure under the assumption that the Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP) is hard for classical computers. That is, it takes a normal computer an extraordinaire (non-polynomial) ammount of time to find the solution to the discrete logarithm. The discrete logarithm problem is defined as follows:

Given a prime number $$p$$, a base $$g$$ (a primitive root modulo $$p$$), and a value $$h$$, find the exponent $$x$$ such that $$g^x ≡ h\ mod\ p$$.

However, in 1994, Peter Shor published what is now known as Shor’s algorithm, a groundbreaking quantum algorithm capable of efficiently factoring the prime factors of integers [1], which can be extended to finding solving the DLP. While the algorithm itself was slow on classical computers, by leveraging quantum quantum Fourier transforms, a quantum computer is capable of finding the solution in $$(\log N)^{2}(\log \log N)(\log \log \log N)$$ time. That is, a polynomial (and rather “fast”) time.

While I do not have the time to fully explain Shor’s algorithm, I recommend this video by minutephyisics: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lvTqbM5Dq4Q

With Shor’s algorithm, it is conceivable that in the coming years, as quantum computers become more stable and capable of handling more qubits, attackers could exploit them to compromise internet security. In fact, it is likely that malicious actors today are already storing encrypted data with the intention of decrypting it in the future when quantum computing resources become available.

With the entirety of classical asymmetric cryptography in jeopardy, a new field has emerged: post-quantum cryptography. This field focuses on developing cryptographic algorithms that are resistant to both classical and quantum computers. Instead of relying on the hardness of problems like the discrete logarithm problem (DLP), which quantum computers can solve efficiently, post-quantum cryptography uses problems that, to our current knowledge, remain computationally difficult for both classical and quantum systems.

One of these very hard mathematical problems is called the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP) in Lattice structures. In mathematics, a lattice refers to a regular arrangement of points in a multi-dimensional space, extending infinitely in all directions. Think of it as a grid that can be formed by combining integer multiples of a set of basis vectors. These basis vectors define the fundamental building blocks of the lattice.

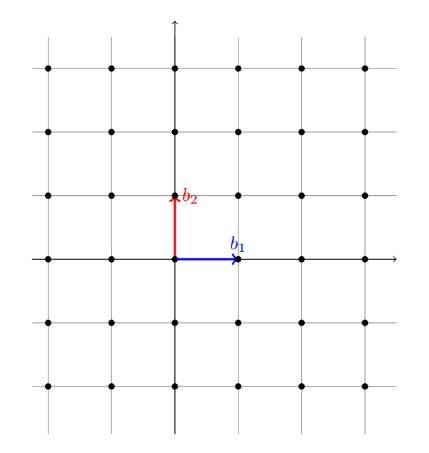

For example, in two-dimensional space (2D), a lattice can be visualized as a grid formed by extending infinitely in both horizontal and vertical directions, with each point on the grid being an integer combination of two chosen vectors, like that seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Lattice $$ℤ^2$$ with basis (0,1) and (1,0) by [2].

Figure 1. Lattice $$ℤ^2$$ with basis (0,1) and (1,0) by [2].

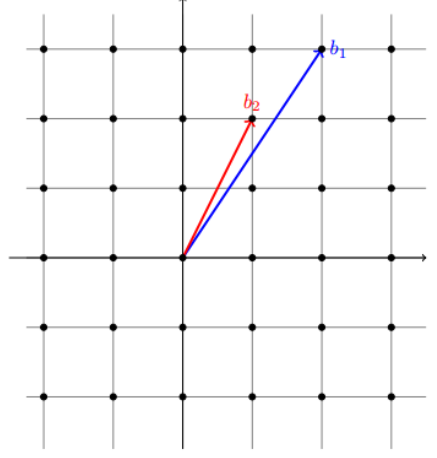

Note that the same Lattice can be represented by a different basis of vectors, such as seen in Figure 2. Therefore, it is possible to create an “easy” lattice by picking a basis, then creating a second “messy” basis that makes the Lattice harder to solve. This intuitive approach will be important to understand how the SVP problem works.

Figure 2. The same Lattice $$ℤ^2$$ with basis (1,2) and (2,3) by [2].

Figure 2. The same Lattice $$ℤ^2$$ with basis (1,2) and (2,3) by [2].

The Shortest Vector Problem (SVP) is a fundamental challenge within lattice-based cryptography. It involves finding the shortest non-zero vector within a given lattice. Formally, given a lattice defined by its basis vectors, the goal is to identify a lattice point that has the smallest Euclidean norm (length) among all non-zero lattice points.

For instance, imagine you have a lattice defined by two basis vectors in 2D. The SVP asks to find the lattice point that is closest to the origin (0, 0) in terms of Euclidean distance.

The difficulty of the SVP lies in its computational complexity, especially as the dimensionality of the lattice increases and the basis vectors become larger. Finding the shortest vector in high-dimensional lattices can be extremely challenging and is believed to be computationally hard for both classical and quantum computers. This hardness is the basis of many of the post-quantum cryptographic algorithms proposed today, including the New Hope.

The next concept one needs to understand is Learning With Errors, and more specifically, Ring Learning with Errors.

3. The Basics of Ring Learning-With-Errors

So far, I’ve shown how assymetric cryptography worked, why quantum computers may break today’s security, and the new mathematical problem that could be used as a basis for our new quantum-safe cryptography. However, this explanation has been - so far - very theoretical: having a difficult problem to base ourselves in doesn’t mean we have found a good way to apply it. In this section, we’ll look at one of the ways that we can transform this concept into a way of transmitting information.

3.1 The Learning with Errors (LWE) Problem

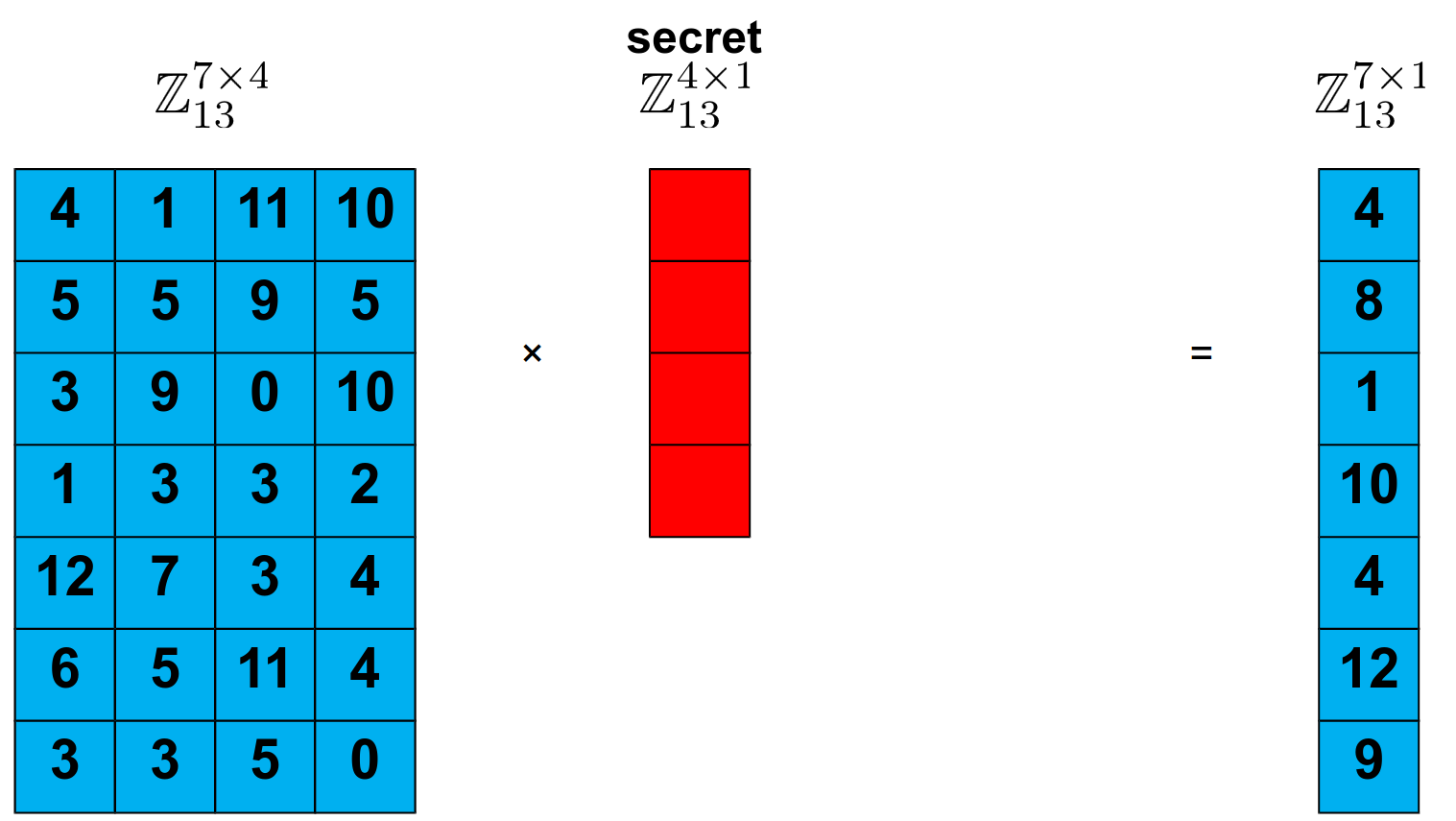

First of all, I’ll need you to forget (briefly) about the explanation I’ve just given about Lattices - and focus on how we could send and retrieve information on computers. If your mind directly thought about matrices, you’re in luck. Imagine I have an array of numbers, and an secret vector (which I’ll use as a private key). If I multiple one by the other, I can have a third vector that contains information about both these numbers, right?

Figure 3. A simple linear system, where blue is given (or public), and red is our secret, by [3].

Figure 3. A simple linear system, where blue is given (or public), and red is our secret, by [3].

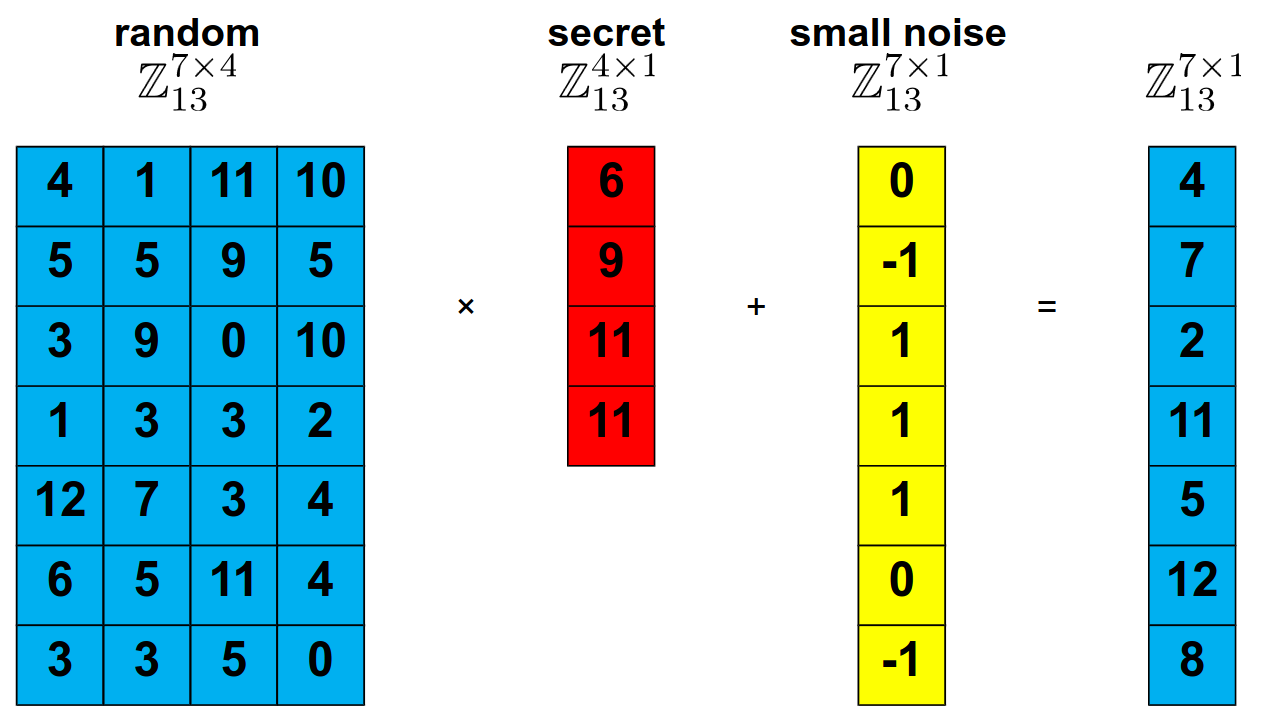

Well, this problem is very easy to solve. It’s a set of linear equations that can be solved with Gaussian elimination, right? An attacker could easily discover the contents of our secret vector. But what if we were to introduce some… unpredictability into it? Let’s say we can add a small vector with random “errors” to mess or resulting array a little.

Figure 4. A simple linear system, where blue is given (or public), and red is our secret, and yellow are just random errors, by [3].

Figure 4. A simple linear system, where blue is given (or public), and red is our secret, and yellow are just random errors, by [3].

By adding this simple array of errors, we’ve turned a deterministic set of linear equations into an system that is impossible to be solved. There is no deterministic way for an attacker to find the values of our secret without resorting to some heuristic.

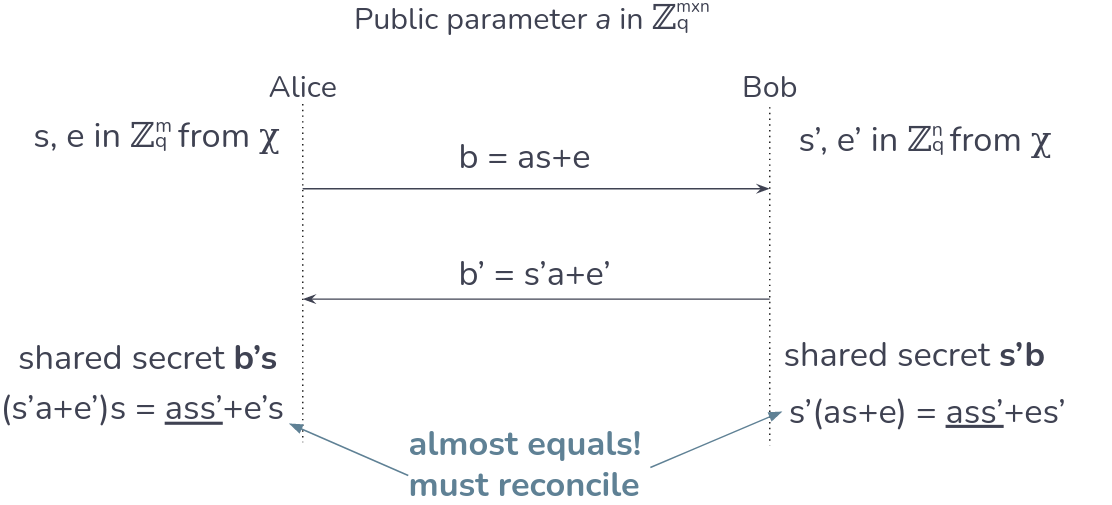

This is the idea behind Learning with Errors (LWE), and this - combined with the idea of the SVP - is the basis of our new cryptography. LWE was introduced by Oded Regev in 2005, the LWE problem involves solving systems of linear equations that are perturbed by small random errors. Specifically, the problem can be described as follows: given a set of linear equations with added noise, the goal is to recover the original linear relationships or the secret vectors used to generate them. Mathematically, this can be expressed as finding a vector $$s$$ given pairs $$(A,b=As+e)$$, where $$A$$ is a matrix, $$s$$ is the secret vector, and $$e$$ is the error vector.

The difficulty of the LWE problem lies in the noise $$e$$, which makes it computationally hard to determine the exact vector $$s$$. Usually, we’ll say that the values of $$e$$ and $$s$$ are sampled from an error distribution $$χ$$ (usually, a gaussian distribution). LWEs, in fact, can be translated into Lattice structures - and finding the secret vector is as hard as finding the shortest vector. In other words, LWE and it’s variants have hardness reductions to certain lattice problems. Thus, breaking an encryption scheme like LWE is at least as hard as solving the corresponding lattice problems (for certain lattices). Since we know solving the corresponding lattice problems is hard, breaking LWE must be hard as well. If you desire to understand more about the mathematical properties behind this, I’d recommend reading this 2016 survey by Peikert [4].

3.2. Public Key Encryption and Key Exchange Methods with LWE (Practical examples)

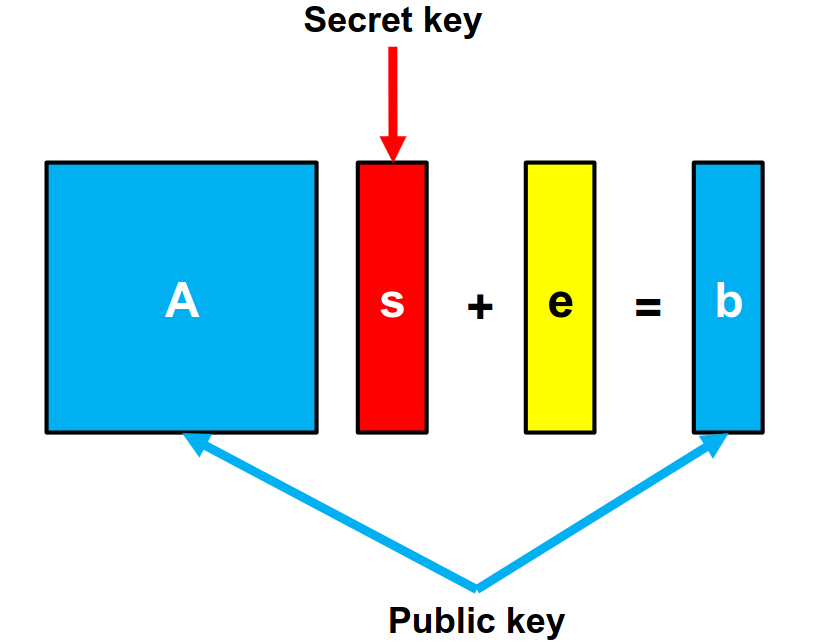

While New Hope doesn’t precisely mirror the Public Key Encryption method described below, understanding it may help understand how LWE works in practice. Imagine I have a public matrix A, a secret s and an error e that togheter generate a vector b. I’ll let both A and b be public.

Figure 5. Generating a public key using LWE by [3].

Figure 5. Generating a public key using LWE by [3].

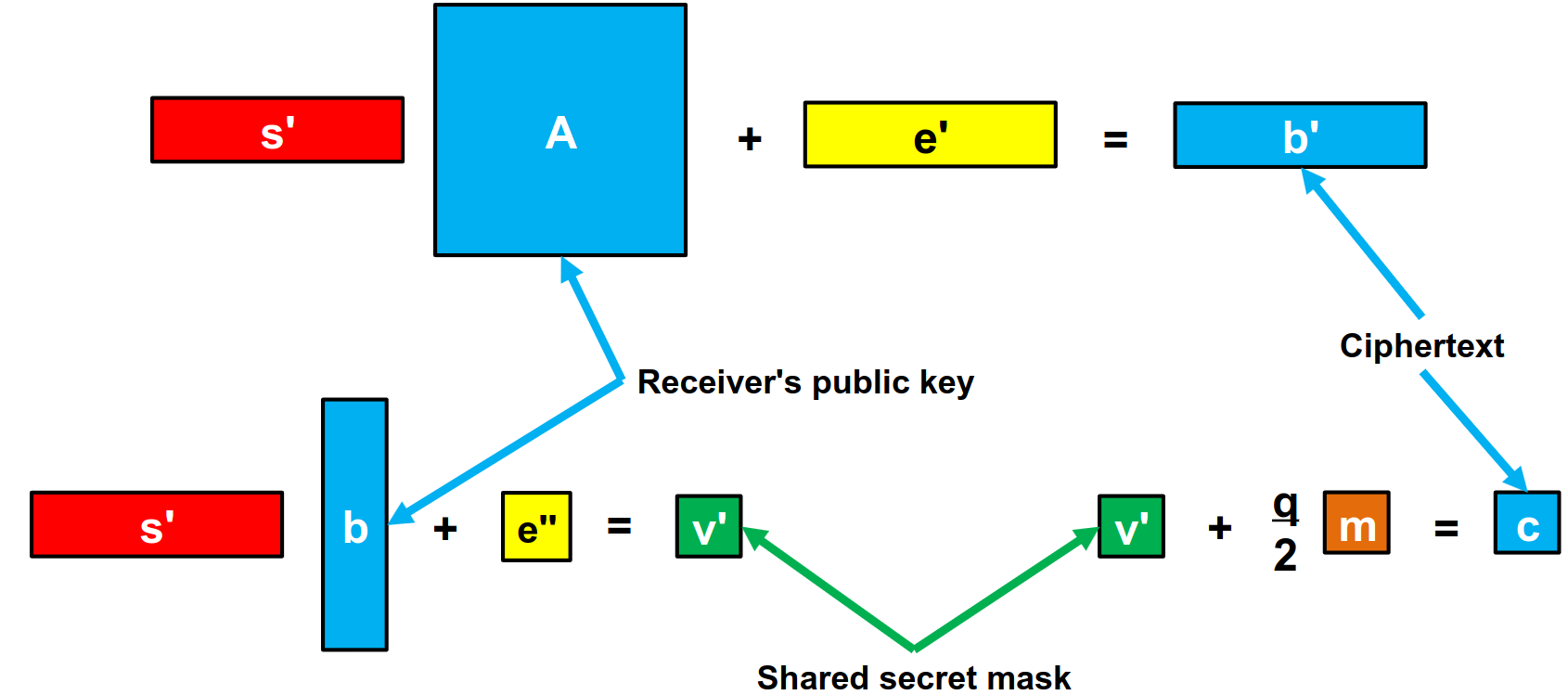

Now, whenever someone wants to send me an encrypted message, they’ll use their secret key s’ and error vector e’, and my public matrix A to generate a new b’ vector. They’ll also give me a hand by generating a shared secret mask by using the b vector I’ve sent them.

Figure 6. Encrypting information using public (A,b = As+e) using LWE by [3].

Figure 6. Encrypting information using public (A,b = As+e) using LWE by [3].

Then, the person who wants to communicate with me will send the b’ and v’ they generated.

Figure 7. Decrypting (b’, v’) using LWE by [3].

Figure 7. Decrypting (b’, v’) using LWE by [3].

In the end, the sender would have sent v’ = s’(As+e)+e’’ = s’As + (s’e+e’’) ≈ s’As, and I would have received v = (s’A+e’)s = s’As+(e’s) ≈ s’As. Notice how these two messages are almost equal, bar the supposedly small errors we introduced. Later, we’ll see how the reconciliation algorithms work for both users to have the same message.

Below, I’ve made a small collection of some links to William Buchanan’s very good interactive websites, where he shows the code and the simulation of a few (simple) LWE instances:

- Basic LWE and introduction to RLWE: https://asecuritysite.com/pqc/lwe_output

- LWE Simulator: https://asecuritysite.com/encryption/lwe

- Another LWE Simulator: https://asecuritysite.com/encryption/lwe2

- Multibit Public Encryption: https://asecuritysite.com/encryption/lwe3

In the near future, I want to also add here on the site my version of these python applications. Finally, the idea behind Key Exchange becomes easy:

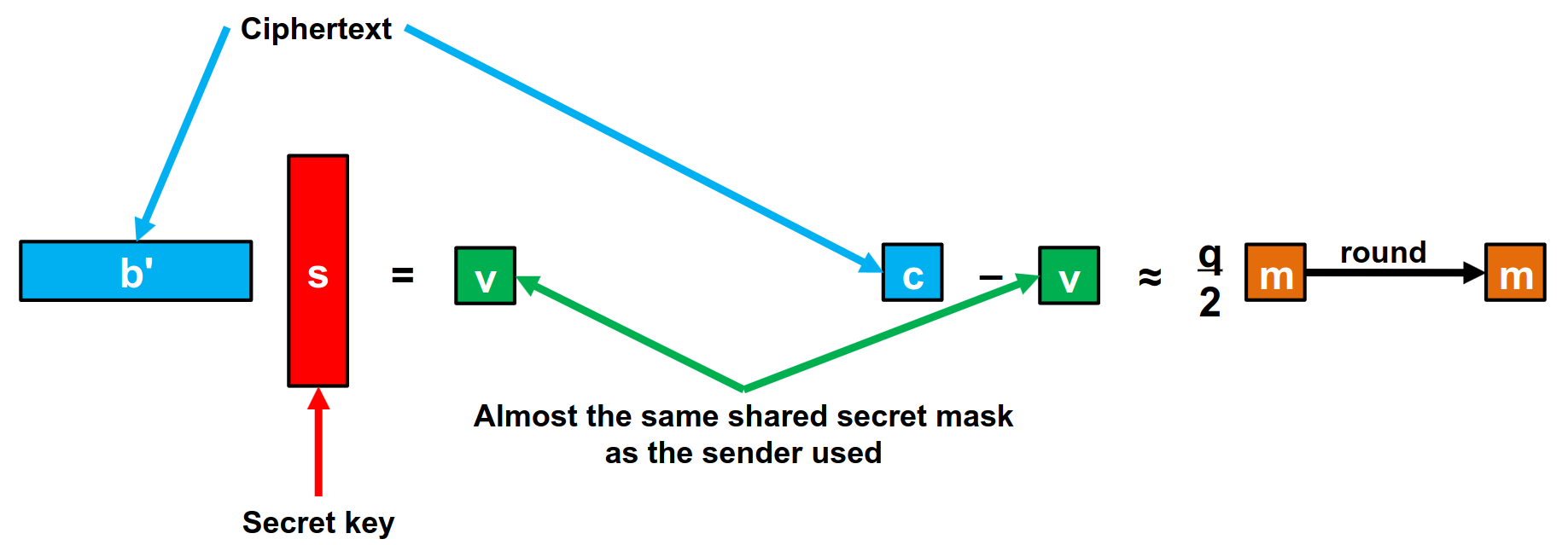

Imagine two people, Alice and Bob. Both have secret keys and want to share between themselves:

Figure 8. Key Exchange in LWE, made by me based on [3].

Figure 8. Key Exchange in LWE, made by me based on [3].

Thus, we have finally created a new (theoretical) way of exchanging keys that is quantum secure.

3.4 The Ring Learning with Errors (Ring-LWE) Problem

The Ring Learning with Errors (Ring-LWE) problem is an extension of the LWE problem, adapted to the structure of polynomial rings. Basically, we keep the same problem structure but now our arrays and matrices use ring polynomials. This improves the efficiency and performance of cryptographic protocols because of the Number Theoretical Transforms (NTTs) and other fun mathematics which I don’t have time or knowledge to explain properly. The main idea is similar to LWE but operates within the context of ring operations, making it more suitable for practical implementations in cryptography. The idea of RLWE was introduced in parts by Lyubashevsky, Peikert, Regev in 2010.

The mathematical basis is simple:

- Let $$𝓡_q = ℤ_q\[X\]/(X^n + 1)$$

- Let $$χ$$ be an error distribution on $$𝓡_q$$

- Let $$s ∈ 𝓡_q$$ be secret

- Generate pairs $$(a, as + e)$$ with

- $$a$$ uniformly random from $$𝓡_q$$

- $$e$$ sampled from $$χ$$

I won’t have time to go over polynomial rings, but basically, one must understand that $$ℤ_q$$ is simply a set of numbers modulo $$q$$, and $$(X^n + 1)$$ is an irreductible polynomial that works as a modulo to all polynomials in the system. $$(X^n + 1)$$ is related to the Fourier transformations, where n is a power of 2. This choice of polynomial is hard to explain briefly, and one has to refer to Peikert’s explanation about why some rings are insecure, and why some are secure [5].

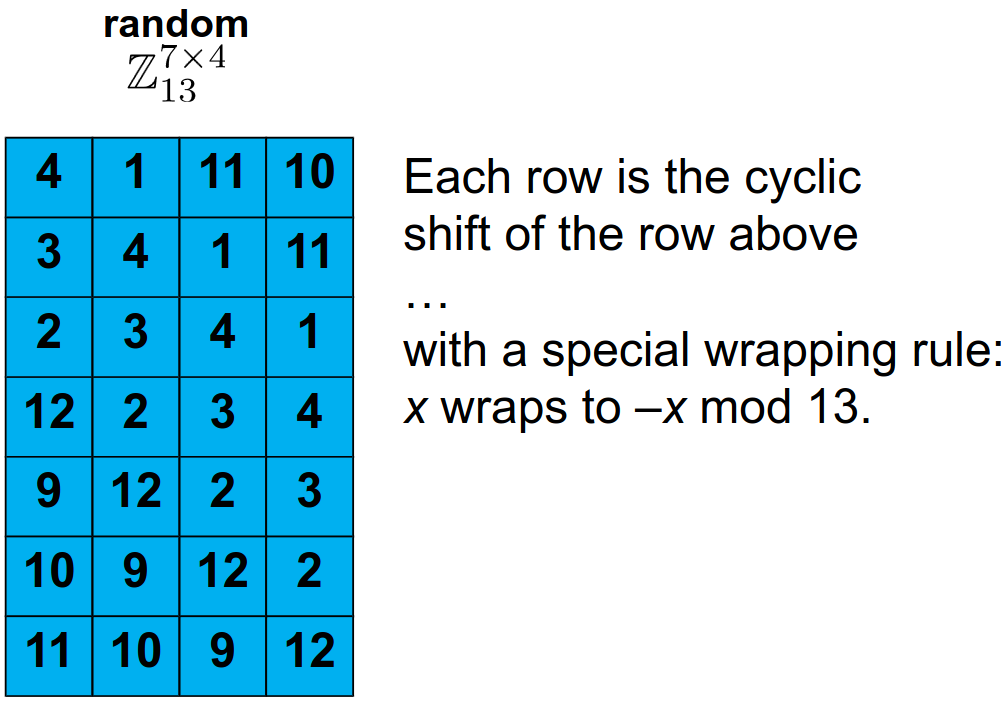

Basically, in order to transform our previous LWE to a RLWE, we can transform or matrix by:

Figure 9. Ring LWE matrix A by [3].

Figure 9. Ring LWE matrix A by [3].

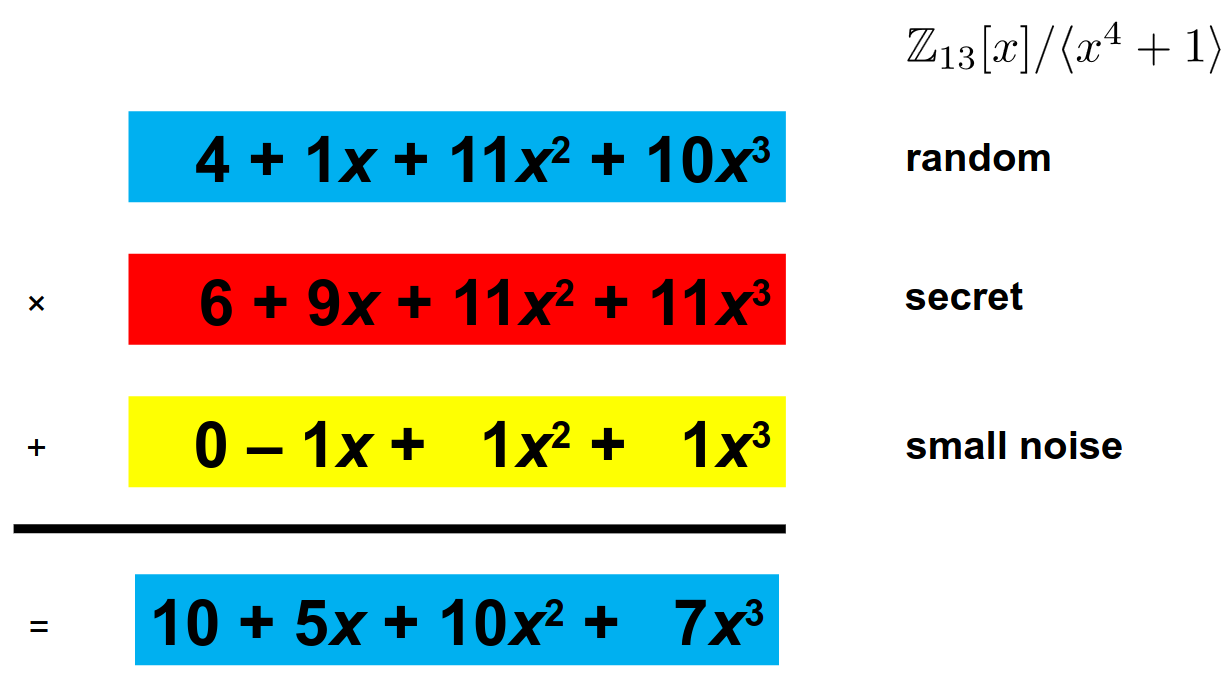

Since all rows are shifts, we don’t need to send them all - simply send the first row and interpret it as a polynomial. Then, simply we must make our polynomial multiplications and reductions:

Figure 10. Ring LWE generation of b=As+e by [3].

Figure 10. Ring LWE generation of b=As+e by [3].

In the end, what we want is for our coefficients to hold the necessary bit information we want to share. Therefore, in the next section, I’ll present briefly how a Key Exchange using RLWE can use the coefficients to encode a shared key.

In conclusion, the structure of the ring allows for more efficient computations and storage, which translates to faster and more compact cryptographic schemes compared to standard LWE - but both work based on the same principle. Therefore, from this point on, I’ll treat LWE and RLWE as interchangeable.

3.5 Reconciliation Algorithms

Previously, we mentioned that when using LWE, both actors will end with similar but slightly different results due to the introduced errors. Therefore, Bit reconciliation algorithms play a critical role in lattice-based key exchange protocols, particularly in ensuring that two parties can securely and efficiently agree on a shared secret key over an insecure channel. These algorithms are essential for correcting errors that arise during the key exchange process, especially when dealing with noisy data as is common in lattice-based schemes.

There are a few ways of reconciling information. Here, I’ll present the classical methods because when we get to New Hope - it will be easier to understand their contribution.

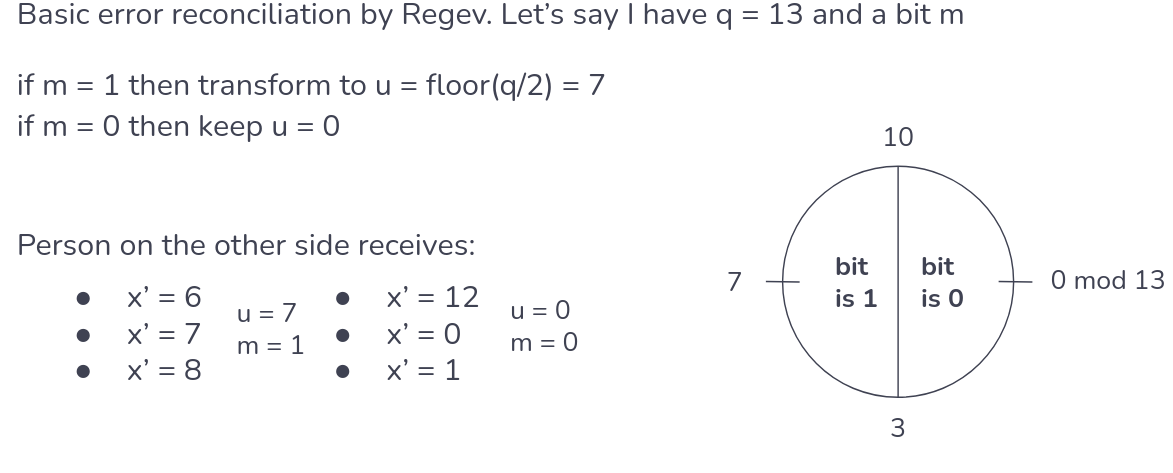

Initially, Regev introduced a simple reconciliation system with no additional information. After sharing the secrets, both parties would round up the (integer) coefficients to bits. That is, as each coefficient of polynomial is an integer modulo q, then we can round each coefficient to either to 0 or 1. Regev’s suggested to round every coefficient if it in $$(−q/2,−q/4]∪(q/4,q/2]$$ to 1, and round to 0 if it is in $$(−q/4,q/4]$$ [3]. Consider that we have only a 1-bit message m, which we’ll transform into coefficient u and a prime q = 13:

Figure 11. Regev’s simple reconciliation system with one bit by me, based on [3].

Figure 11. Regev’s simple reconciliation system with one bit by me, based on [3].

Now, it becomes easier to expand this to multiple coefficients. Imagine that Alice and Bob shared keys of 4 bits with q = 13. Alice ended with something close to $$12x^0 + 7x^1 + 1x^{2} + 6x^{3}$$, which can be easily rounded to 0101. Meanwhile, Bob ended with $$11x^0 + 5x^1 + 0x^{2} + 8x^{3}$$, which can too be rounded to 0101.

However, one can imagine that sometimes the errors are a little bit too much and these keys do not end the same. Researchers found that the probability of failure of this is approach is $$2^{-10}$$.

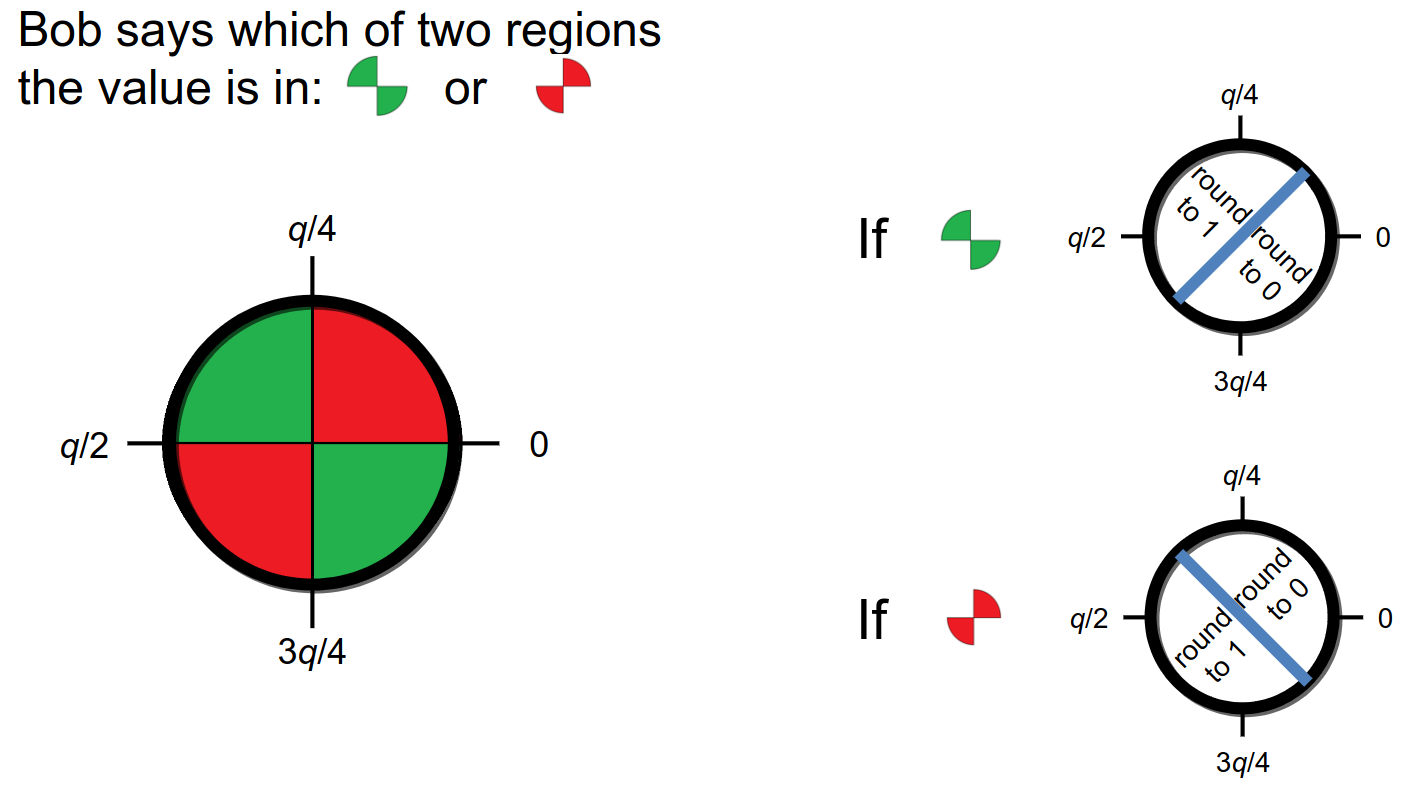

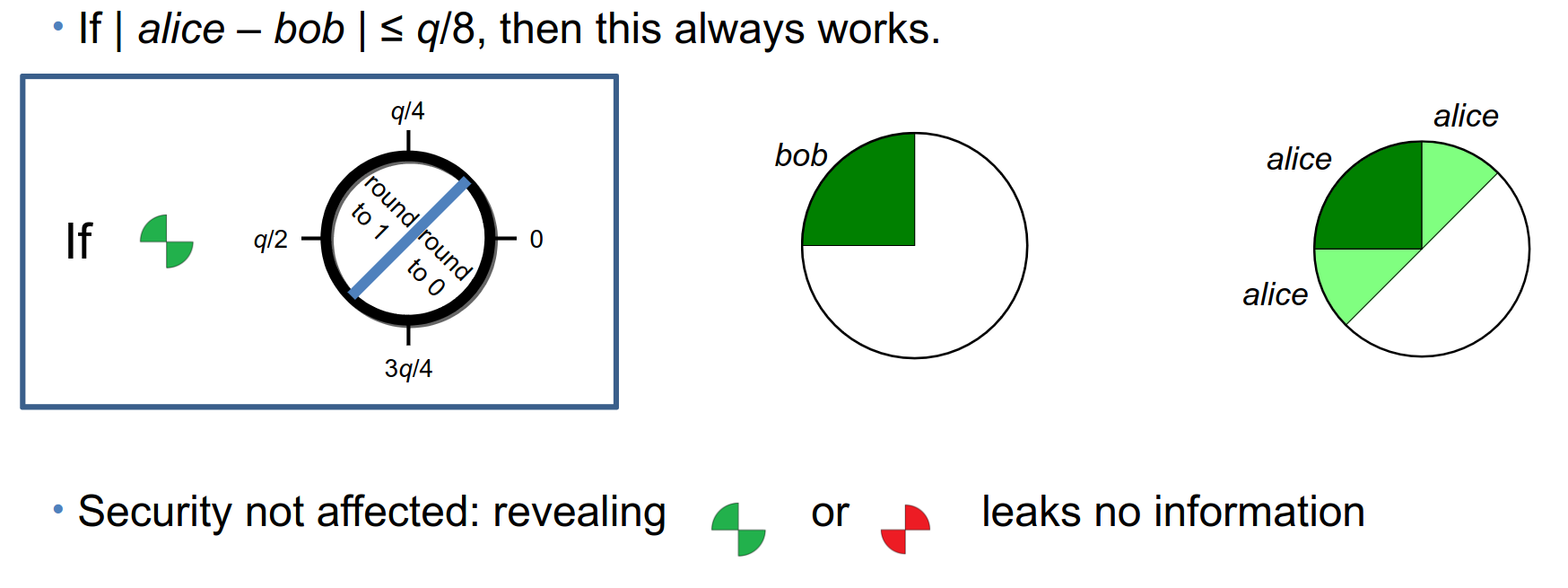

Therefore, researchers started looking for ways to improve this reconciliation - and they came up with the idea of reconciliation information. The idea is that one actor can send the other some information to help find round the bits. This information should also be based on a LWE vector, thus, turning into a pseudo-random information (i.e., it shouldn’t leak any information regarding the secret keys). Peikert’s idea in 2014 was introducing an additional bit which revealed which fourth of the modular wheel the original bit was [6]. That is:

Figure 12. Peikert’s 2014 [6] approach to reconciliation, drawing made by [3].

Figure 12. Peikert’s 2014 [6] approach to reconciliation, drawing made by [3].

By sending this information, it becomes easier for any of the two actors to reconcile their bits, without revealing any information (after all, the original coefficients look random, and the quarter information appears as a random 50% chance to both sides).

Figure 13. Peikert’s 2014 [6] approach to reconciliation, with the overlap between both Alice and Bob. Drawing made by [3].

Figure 13. Peikert’s 2014 [6] approach to reconciliation, with the overlap between both Alice and Bob. Drawing made by [3].

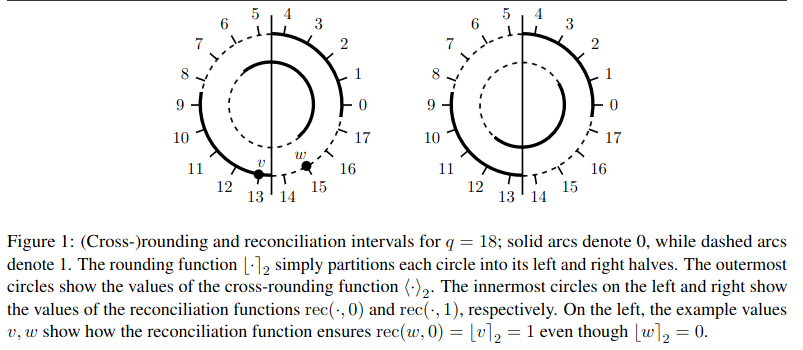

It was this idea by Peikert, and his 2014 paper of how RLWE could be used to exchange keys in the internet that gave rise to the two proposals for Post-Quantum TLS that we’ll see today. In special, I’ll bring the reader’s attention to Peikert’s rounding notation as shown in his paper:

Figure 14. Peikert’s 2014 [6] notation for both rounding (similar to Regev’s approach), and cross-rounding (his quarter-based approach).

Figure 14. Peikert’s 2014 [6] notation for both rounding (similar to Regev’s approach), and cross-rounding (his quarter-based approach).

Both notations will appear in the BCNS proposal for TLS, therefore, I thought it would be interesting for the reader to know them.

4. New Hope TLS Proposal

4.1 Overview of TLS and the BCNS Proposal for TLS

Transport Layer Security (TLS) is a widely used cryptographic protocol designed to provide secure communication over a computer network. TLS ensures privacy, data integrity, and authentication between communicating applications. It is the successor to the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) protocol and is commonly used to secure web traffic, email, instant messaging, and other forms of data transmission.

TLS works through a series of steps known as the TLS handshake, which establishes a secure session between a client (such as a web browser) and a server (such as a web server). The handshake involves the following key processes:

- Negotiation of Security Parameters: The client and server agree on the version of TLS to use, select cryptographic algorithms (cipher suites), and establish session parameters.

- Server Authentication and Pre-Master Secret Exchange: The server provides a digital certificate to authenticate its identity. The client then generates a pre-master secret and securely transmits it to the server, typically encrypted using the server’s public key.

- Session Key Generation: Both parties use the pre-master secret along with other data exchanged during the handshake to generate a symmetric session key, which will be used to encrypt and decrypt data during the session.

- Secure Data Transmission: Once the handshake is complete and a secure session is established, the client and server can exchange data encrypted with the session key, ensuring confidentiality and integrity.

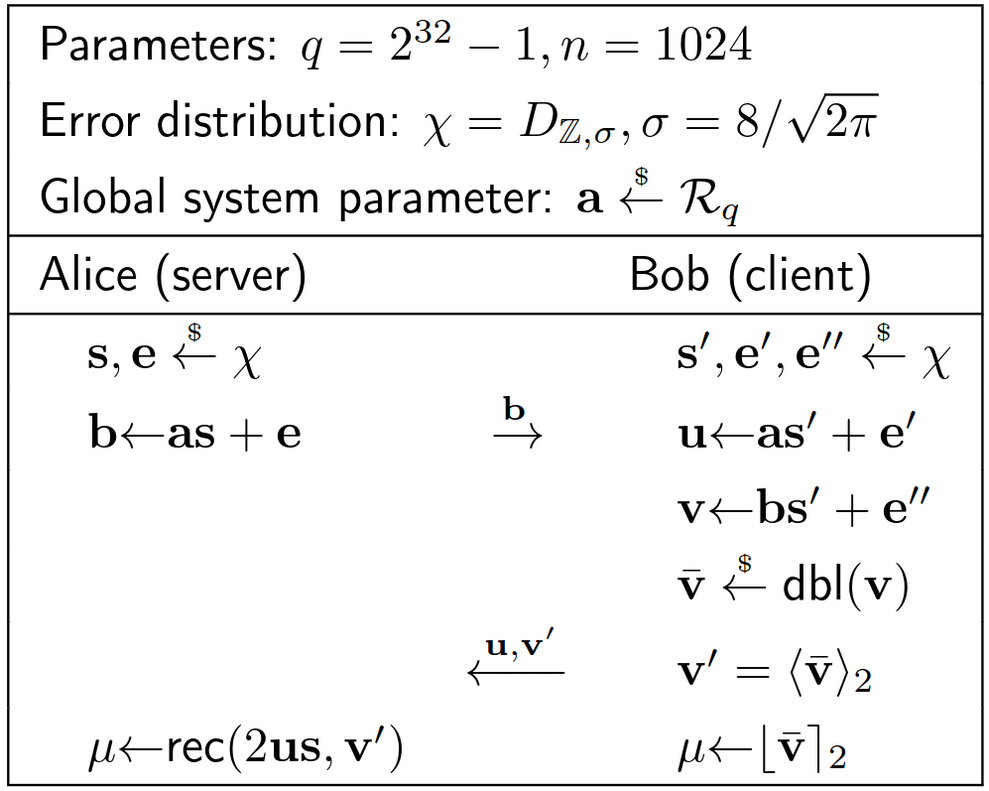

Previously, TLS relied on assymetric cryptography functions, such as elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman, which we already explained are vulnerable to quantum computers. Therefore, based on Peikert’s paper, Bos, Costello, Naehrig, and Stebila (BCNS) proposed a new way of exchanging keys [7].

It is quite straightforward to understand the BCNS with the knowledge we already have. First of all, BCNS instantiated their ring as:

- Let $$𝓡_q = ℤ_q\[X\]/(X^n + 1)$$

- Where $$n = 1024$$ and $$q = 2^{32}-1$$

- $$χ$$ is a discrete Gaussian $$χ = D_{ℤ,σ}$$ where $$σ = 8/2π$$

Alice (the server) will generate b = as+e as we explained previously, and Bob will do the same with his with his secret key and errors (now b’ has changed to u).

Figure 15. The BCNS key exchange method for TLS [7].

Figure 15. The BCNS key exchange method for TLS [7].

Finally, in order to reconcile errors, BCNS makes the client (Bob) use some functions created by Peikert to round $$\bar{v}$$ and send a reconcilation information $$v'$$ to the server.

At the end of this exchange, both Bob and Alice end up with the following keys:

- Alice has 2us = 2ass′ + 2e′s

- Bob has v ≈ 2v = 2(bs′ + e′′) = 2((as + e)s′ + e′′) = 2ass′ + 2es′ + 2e′′

Which, as explained previously, will yield (given a margin of error), the same shared secret, which they can use as a symetric key to exchange information. The claimed security level by BCNS is 128 bits.

However, it should be noted that the BCNS proposal still didn’t have a formal security analysis, nor it had an optmized implementation to be useful in real-life applications. Plus, depending on certain design decisions, it could be vulnerable to some attacks. All these topics were what led to the next proposal: New Hope [8].

4.2. The Design of New Hope

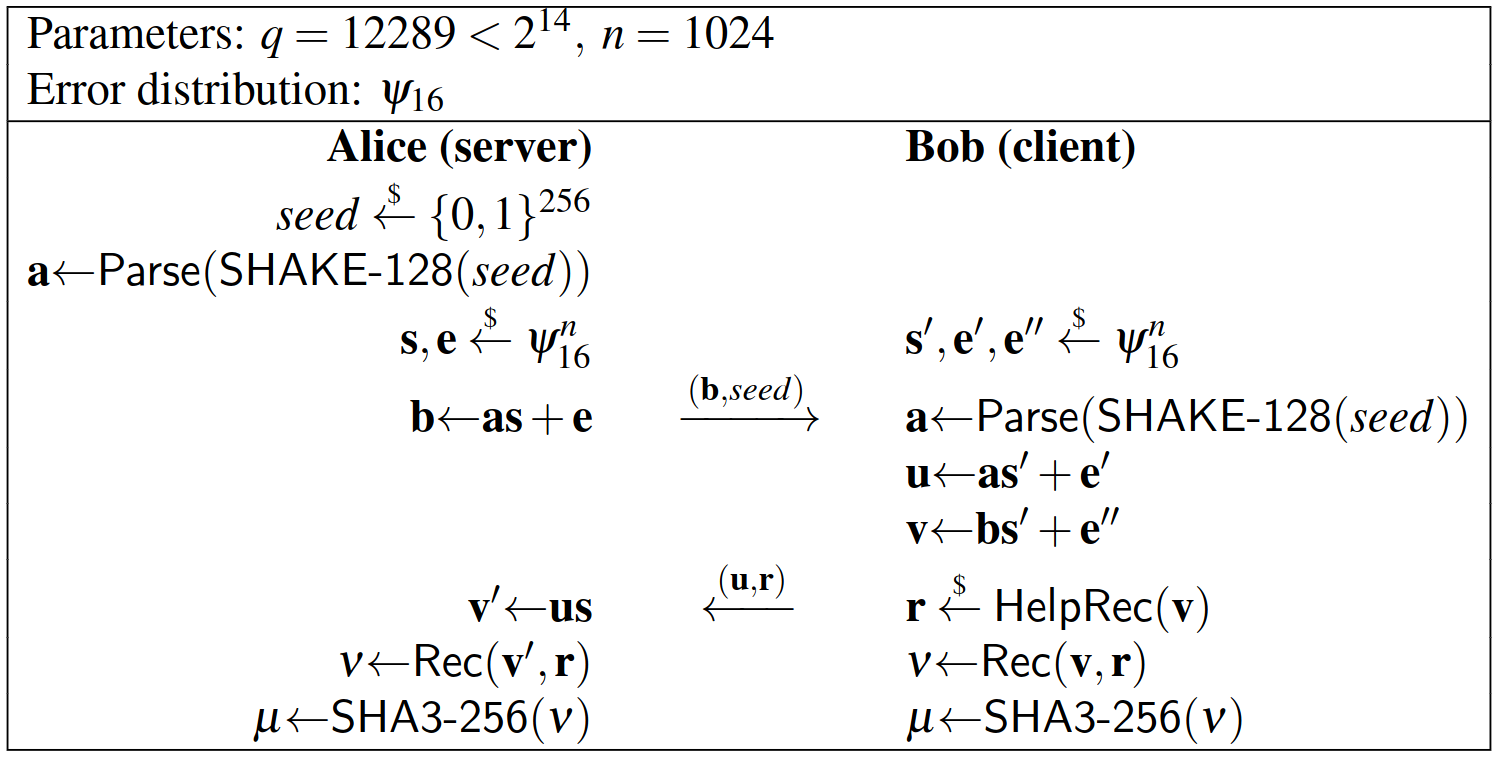

The New Hope proposal is an improvement of the BCNS proposal. Published in 2016 by the “CryptoJedis” Alkim, Ducas, Poppelmann, and Schwabe, it was submitted to the NIST PQC standardization process, where it was approved up to the 2nd phase. The main contributions of the proposal are:

- Improve failure analysis and error reconciliation

- Choose parameters for failure probability ≈ $$2^{−60}$$

- Keep dimension n = 1024

- Drastically reduce q to $$12289 < 2^{14}$$

- Encode polynomials in number-theoretic transform (NTT) domain

- Optimized implementation in C.

- Higher security, shorter messages, and speedups

Here, it should be noted that the reduction of q is very important, because not only does it increases efficiency, but q was chosen in such a manner that it was the smallest prime for which it holds that $$q ≡ 1\ mod\ 2n$$ so that the number-theoretic transform (NTT) can be realized efficiently and that we can transfer polynomials in NTT encoding)

To start, the first step in implementing a secure TLS system was deconstructing the public value $$a$$. Up until this point, we treated $$a$$ as a publically available, fixed value - and in proposals like BCNS, it could be set by the server only once and used many times.

The problem with this approach is that a malicious server could choose an $$a$$ where a backdoor could be exploited. By choosing $$a = gf^{−1}\ mod\ q$$, where $$g$$ and $$f$$ are small chosen values that $$f = g = 1\ mod\ p$$ (the complete proof can be seen in the paper). This is similar to a previous attack called LogJam.

The second problem is that a fixed $$a$$ could be eventually broken by an attacker. For example, a server could set a public $$a$$ that will only be replaced after two years of use - however, an attacker with a powerful computer could try to find good lattice bases for a after one year of computation. In this scenario, even if the mathematical properties of the LWE are good, the design choice of leaving $$a$$ static for a long time allowed a non-polynomial attacker to gain advantage. This is called a all-for-the-price-of-one attacks.

The solution to both of these design problems is that $$a$$ should always be generated in every new connection. While this would decrease optimization at first, the New Hope proposal created a way that a random seed and a SHAKE-128 hash algorithm can automatically generate the public parameter $$a$$. Therefore, not only is $$a$$ no longer vulnerable to malicious servers, but it is also re-generated every connection.

The New Hope approach also disables any key-caching (something common in the current Diffie-Hellman approach in TLS). While it is possible (but not desirable) to cache $$a$$ for a few hours, it is undispensable that secrets secrets s, e, s′, s′, e′′ should be regenerated every connection.

The next step in optimization was changing the discrete Gaussian distribution $$χ$$ into a simple binomial distribution $$ψ$$. In the paper, the authors prove that a binomial approach is much easier to implement on computers without sacrificing much in security. Figure 16 shows the New Hope Key Exchange:

Figure 16. New Hope Key Exchange [8].

Figure 16. New Hope Key Exchange [8].

It is easy to see that there is not a lot of change between figure 15 (BCNS) and figure 16 (New Hope). The parameter $$a$$ is now generated randomly, but its use continues to be the same. The sampling of both s and e now are from a binomial distribution $$ψ$$, and the reconciliation functions have been tweaked - where Bob will send a reconciliation vector $$r$$ to the server.

At the end of the exchange, both Alice and Bob end up with:

- Alice: v′ = us = ass′ + e′s

- Bob: v = bs′ + e′′ = (as + e)s′ + e′′ = ass′ + es′ + e′′

4.2. New Hope’s reconciliation functions

At this point, we’ve already seen the core of the New Hope proposal: how (and why) it works, the design considerations that led to it, and how the key exchange happens. However, another contribution to the optimization was the new reconciliation method.

First of all, New Hope works with polynomials of size n = 1024, however, the shared symmetric key they want to generate has a size of 256 bits. Their idea main idea, based on previous findings by other scientists (Pöppelmann and Güneysu), is to encode 1 bit of the shared key every 4 coefficients of the polynomials. This increases security by reducing the chance of error in reconciliation. Following the Paper’s explanation, I’ll explain the concept in 2 dimensions, before we continue to 4 dimensions.

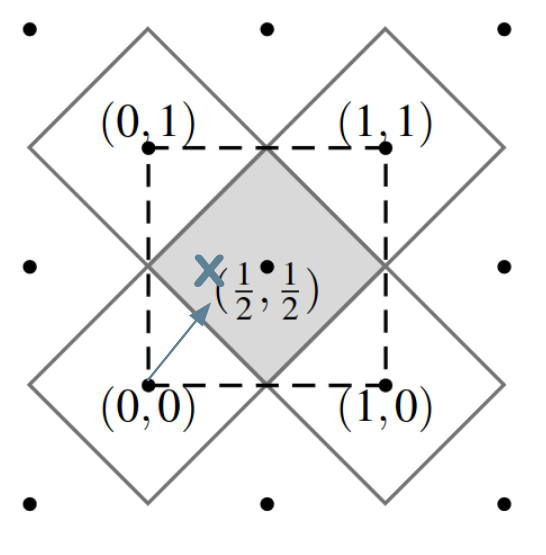

Figure 17. The $$\tilde{D}_2$$ Lattice Voronoi cells, with an x vector painted by me [8].

Figure 17. The $$\tilde{D}_2$$ Lattice Voronoi cells, with an x vector painted by me [8].

First assume that both client and server have the same vector $$x ∈ [0, 1)^2 ⊂ ℝ^2$$ and want to map this vector to a single bit.

Consider the lattice $$\tilde{D}_2$$ with basis $${(0, 1),(½, ½)}$$. The possible range of the vector x is marked with dashed lines. Mapping x to one bit is done by finding the closest-vector $$v ∈ \tilde{D}_2$$.

If $$v = (½, ½)$$ (i.e., x is in the grey Voronoi cell), then the output bit is 1; if v ∈ $${(0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0), (1, 1)}$$ (i.e., x is in a white Voronoi cell) then the output bit is 0.

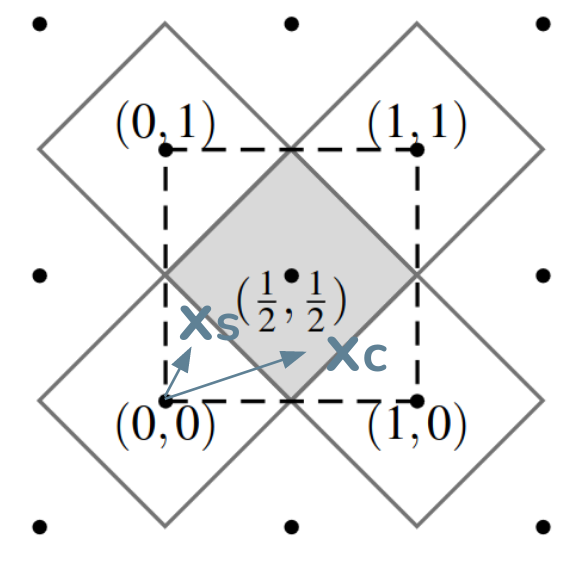

Now recall that client and server only have a noisy version of x, i.e., the client has a vector $$x_c$$ and the server has a vector $$x_s$$. Those two vectors are close, but they are not the same and can be on different sides of a Voronoi cell border. How can we fix that?

Figure 18. The $$\tilde{D}_2$$ Lattice Voronoi cells, with client and server x vectors painted by me [8].

Figure 18. The $$\tilde{D}_2$$ Lattice Voronoi cells, with client and server x vectors painted by me [8].

What if the client sent the distance from its vector to the center of the cell as a reconciliation information? The server can add this difference to get closer to the center as well. Remember: this information is created from what seems like a pseudo-random matrix, therefore, it doesn’t reveal any information from the true nature of x.

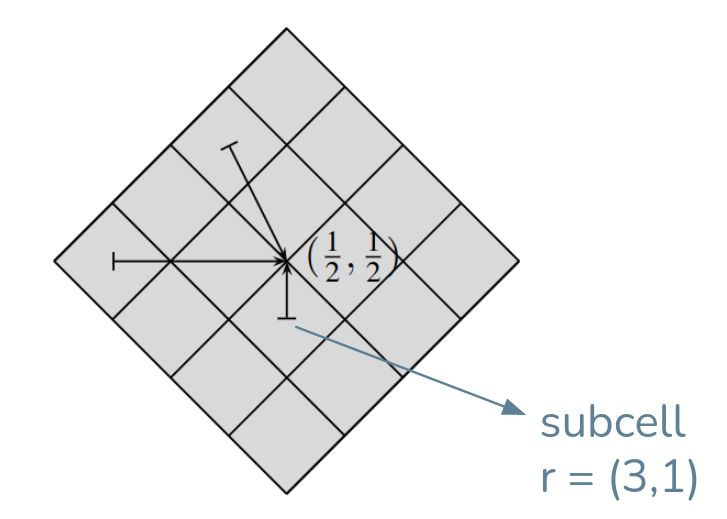

Well, we could stop our reconciliation here, but one can optimize it even further: Every Voronoi cell can be divided into quadrants like the figure below. In this 2-D approach, we will divided it into 16 subcells:

Figure 19. The central voronoi cell divided into 16 subcells. I’ve painted in blue the example of where an x vector could be found [8].

Figure 19. The central voronoi cell divided into 16 subcells. I’ve painted in blue the example of where an x vector could be found [8].

We can reduce the reconciliation vector by dividing each cell into $$2^{dr}. Only send which subcell our $$x_c$$ is. We’ve reduced our reconciliation information to a simple tuple indicating which subcell our vector is. This is very similar to Peikert’s approach in 2014 and doesn’t spoil any information from the original vector other than its relative position to a subcell.

To expand this idea into 4 dimensions, we must simply imagine that every 4 coefficients of the n = 1024 generate a space $$\tilde{D}_4$$, and our reconciliation vector will be $$r ∈ {0, 1, 2, 3}^4$$ for every coefficient.

There are a few more nuances to this error reconciliation (for example, in the appendix, they present a function that “blurs” the information a little bit more by randomly moving the vector in the diagonal), but in sum, the error reconciliation of New Hope ensures that the Key Exchange works properly.

4.3. New Hope’s Paper other sections and additional material.

So far, we’ve seen sections 1-5 of the New Hope paper. I’ve elected that these were the most important sections to understand the core of the proposal, but for completeness, I’ll comment shortly on the other sections:

- 6.1 Methodology (The Core SVP Hardness): This section explains the core methodology used for analyzing post-quantum security, focusing on the hardness of the Shortest Vector Problem (SVP), which we explained previously.

- 6.2 Enumeration vs. Quantum Sieve: This section compares two methods for solving SVP: heuristic algorithms for approximate solutions (enumeration) and quantum algorithms for exact or near-exact solutions (quantum sieve). It evaluates their effectiveness and computational demands.

- 6.3 Primal Attack: This section discusses the primal attack, where a unique-SVP instance is derived from the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem and solved using the BKZ algorithm. It estimates the required computational resources, expressed as best-known quantum cost (BKC: $$2^{0.265n}$$) and best-plausible quantum cost (BPC: $$2^{0.2075n}$$).

- 6.4 Dual Attack: This section examines the dual attack, another strategy to break New Hope TLS by exploiting different aspects of the LWE problem and the lattice structure. It assesses the computational effort needed for such attacks using quantum algorithms.

- 6.5 Security Claims: This section summarizes the overall security guarantees of New Hope TLS against classical and quantum attacks, based on the methodologies and attack vectors analyzed in the previous sections.

Section 7 explains the implementation of New Hope in C, and how to transform the Ring-LWE polynomials in the NTT domain (thus, making all multiplications easier), while Section 8 compares New Hope with BCNS (which we’ll see in the next section). A few other useful links are:

- The website of the New Hope Proposal: https://newhopecrypto.org/

- A python library implementing New Hope: https://github.com/scottwn/PyNewHope

- William Buchanan’s interactive New Hope implementation: https://asecuritysite.com/pqc/newhope

5. Comparison with previous works and conclusions

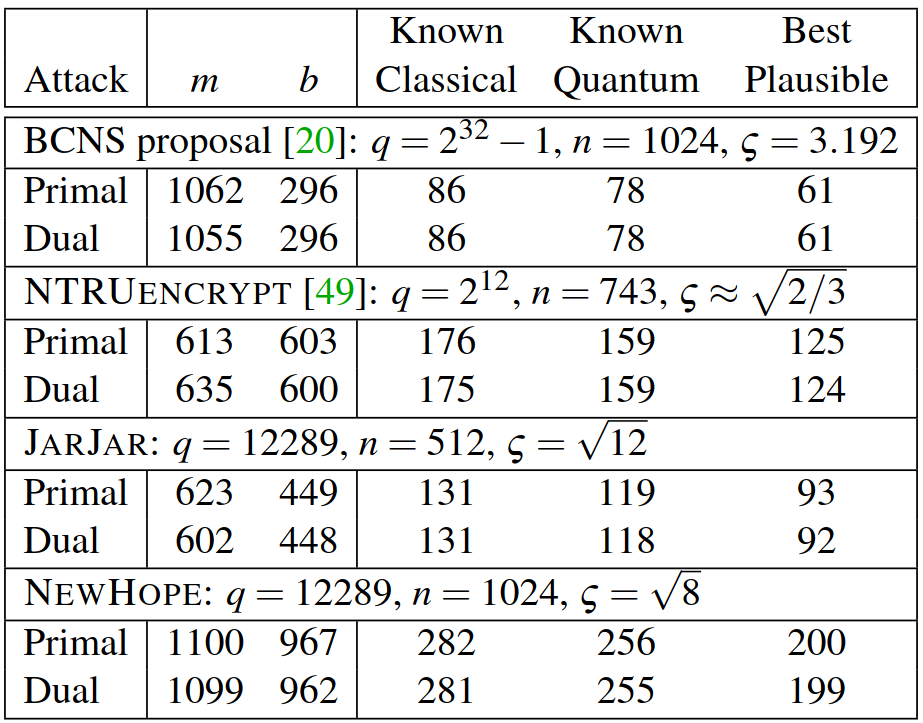

As explained previously, New Hope was capable of both increasing optimization/speed but also increasing security. First, here is the comparison between multiple proposals and New Hope when faced with a Primal Attack using the BKZ algorithm:

Figure 20. “Core hardness of NEW HOPE and JAR JAR and selected other proposals from the literature. The value b denotes the block dimension of BKZ, and m the number of used samples. Cost is given in log 2 and is the smallest cost for all possible choices of m and b. Note that our estimation is very optimistic about the abilities of the attacker so that our result for the parameter does not indicate that it can be broken with $$≈ 2^{80}$$ bit operations, given today’s state-of-the-art in cryptanalysis” [8].

Figure 20. “Core hardness of NEW HOPE and JAR JAR and selected other proposals from the literature. The value b denotes the block dimension of BKZ, and m the number of used samples. Cost is given in log 2 and is the smallest cost for all possible choices of m and b. Note that our estimation is very optimistic about the abilities of the attacker so that our result for the parameter does not indicate that it can be broken with $$≈ 2^{80}$$ bit operations, given today’s state-of-the-art in cryptanalysis” [8].

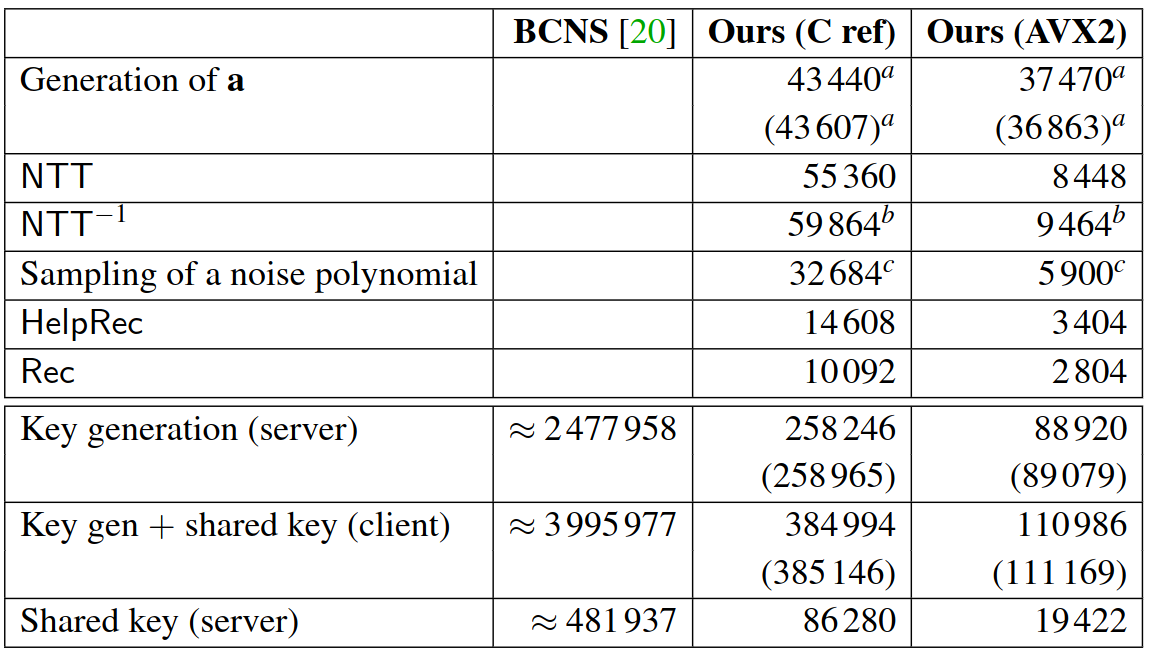

Then, a comparison in speed (cycles) between New Hope and BCNS:

Figure 21. “Intel Haswell cycle counts of our proposal as compared to the BCNS.” [8].

Figure 21. “Intel Haswell cycle counts of our proposal as compared to the BCNS.” [8].

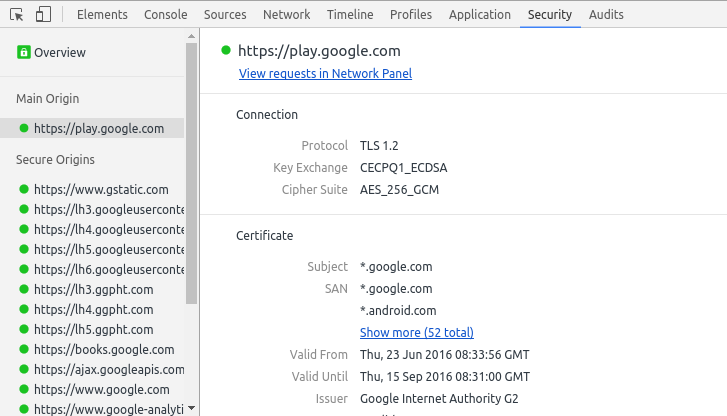

Finally, as a conclusion of the work, in July 7 2016, Google announces 2-year post-quantum experiment where NewHope+X25519 (CECPQ1) were implemented in BoringSSL for Chrome Canary - which was the connection used to access google services.

Figure 22. Screenshot of Google Chrome Canary using NewHope [9].

Figure 22. Screenshot of Google Chrome Canary using NewHope [9].

As for my personal conclusion, I must admit that New Hope was an interesting proposal not only for its design decisions and exceptional reproducibility (unfortunately, not a lot of academics are serious about publishing their code and allowing others to easily replicate their results) but also because of the imense amount of knowledge it helps one acquires while studying it. As I mentioned earlier, I do plan on expanding on this material and helping other people learn about Post-Quantum Criptography.

6. Sources and Additional Material

(Source style may be inconsistent)

[1] P. W. Shor, “Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring,” Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Santa Fe, NM, USA, 1994, pp. 124-134, doi: 10.1109/SFCS.1994.365700.

[2] Hesamian, Seyedamirhossein, “Analysis of BCNS and Newhope Key-exchange Protocols” (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 1485. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1485

[3] Stebila, Doublas. Summer School on real-world crypto and privacy. Šibenik, Croatia (2018). https://www.douglas.stebila.ca/research/presentations or https://summerschool-croatia.cs.ru.nl/2018/slides/Introduction%20to%20post-quantum%20cryptography%20and%20learning%20with%20errors.pdf

[4] Chris Peikert. (2015). A Decade of Lattice Cryptography. https://eprint.iacr.org/2015/939

[5] Chris Peikert. (2016). How (Not) to Instantiate Ring-LWE. https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/351

[6] Chris Peikert. (2014). Lattice Cryptography for the Internet. https://eprint.iacr.org/2014/070

[7] Bos, Costello, Naehrig, Stebila (2015). Post-quantum key exchange for the TLS protocol from the ring learning with errors problem. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7163047

[8] Alkim, Ducas, Poppelmann, & Schwabe (2016). Post-quantum Key Exchange—A New Hope. https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity16/technical-sessions/presentation/alkim

[9] Google Security Blog. https://security.googleblog.com/2016/07/experimenting-with-post-quantum.html

My Google Slides Presentation:

Link: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1VSCpnVRwjiTOwy40ch1YTON-VkPrGlg4mtnDcvuSYeI/edit?usp=sharing

More Links:

- http://web.eecs.umich.edu/~cpeikert/pubs/suite.pdf

- https://math.colorado.edu/~kstange/teaching-resources/crypto/RingLWE-notes.pdf

- https://eprint.iacr.org/2010/613.pdf

- https://eprint.iacr.org/2012/230.pdf

- https://eprint.iacr.org/2014/599.pdf

- https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity16/technical-sessions/presentation/alkim